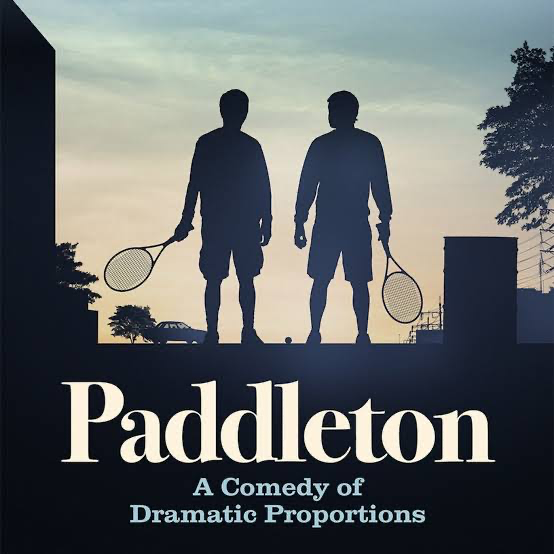

‘I’m the dying guy!” Paddleton (2019) and how to help your dying friend

Paddleton (2019) is an emotional story that explores the tensions between friendship, choice, and suicide.

Paddleton (2019) is an emotional story co-written by Mark Duplass and Alex Lehmann, directed by Lehmann, that explores the tensions between friendship, choice, and suicide.

Michael (played by Duplass) and Andy (Ray Romano) are two best friends living in a suburban condo. They spend their days watching their favourite movie, eating pizza, and playing an invented ball game called Paddleton. Their steady routine takes a drastic turn when Michael decides to commit medical suicide rather than face terminal stomach cancer. Andy struggles to accept this choice, but decides to support his best friend instead.

The movie distinctly ignores taboos around assisted suicide, as the two embark on their first and final road trip together. This is wholesomely non-political unlike many films and books about this topic, for example, ‘Me Before You.’ The world of Paddleton is very small, intimate and emotional because of this choice.

The film lends more screen time to Andy than to Michael, which is unusual for stories depicting terminal illness, which tend to follow the experience of the patient more closely than the bystander. Andy is a perfect point of view, however, as his emotional and physical closeness with Michael means we get to see both sides of the story. We see how Michael’s inevitable death affects the two of them in different ways.

The tensions begin when Andy offers to pay for the medication that will end Michael’s life. When his card declines, he argues, then gives in and lets Michael pay, but promises to pay him back. The moment is painful as it appears the gesture means nothing to Michael. Money is no object to him anymore, he has accepted his fate, so he doesn’t care about being paid back, but Andy clearly hasn’t.

Michael doesn’t understand why Andy is so upset since ‘I’m the dying guy,’ to which Andy replies, cathartically, ‘I’m the other guy!’ The simple gesture conveys his feelings, and he becomes an allegory for those affected by the suicide of a loved one, even one he is sympathetic to. The insincerity Michael has shown toward his fate has been startling, evidence of Duplass’ chilling expressions which are familiar and even endearing to fans of his horror film series ‘Creep.’

What convinced me about this film is the lack of politics, which some would say is a shortcoming when dealing with such a serious subject matter as suicide. It doesn’t pose the question ‘should this be allowed?’ rather ‘how does this affect my friend?’ Andy hardly tries to discourage Michael, understanding without arguing that this is his choice and he won’t be swayed. He doesn’t want his friend to suffer, but he’s not enthusiastic about losing him.

He does, however, stand up for himself. Clearly this film doesn’t advocate for being a bystander in the life of a dying person, but for the value of attention.

bell hooks said it best: ‘Attention is an important resource’ (All About Love) Of course she said this about romantic relationships, and it could be said that the movie depicts a romantic kind of friendship. Paddleton is a breath of fresh air for male characters. In a creative tradition of stoicism where the only mode of showing strong emotion is through a breakdown or climatic outburst, Paddleton gives the audience what we really long for: healthy communication. The conflict, therefore, is not between the two friends, but between them and their situation. This makes them sympathetic, as the audience isn’t put through the trouble of picking sides.

When watching, I couldn’t help but compare the two characters to John Steinbeck’s Tom Joad and Jim Casy (The Grapes of Wrath), sitting together under the shade of a tree and talking about what they were worried about, life, death, religion and money. It was shocking, for a book written in 1939, that raw emotion was put into print as a simple dialogue between two men. It may be a testament to Steinbeck or Duplass, or a critique of myself, that I’ve hardly found another piece of media from the 80 years between the two that successfully did this with the same effect.

When recommending Paddleton, I’ve often mentioned how it feels like you walked past someone in the street and imagined that they have a real life, full of trials and tough decisions just like you. They may not have momentous consequences. They may not ever be famous. They might even only have one friend, one favourite movie or a food they eat every day. In that way, it’s intimate and relatable, and I would be remiss if I didn’t rate it 10/10.